Column: Constitutional Limits on Congressional Investigations Into Palestine-Israel Advocacy

Civil Liberties Union

By Christina Bartson

What does aggressive, discriminatory and abusive policing look like?

The NYCLU asked 30 artists to capture the impact of Broken Windows policing through their artwork. The result is the Museum of Broken Windows, a pop-up experience in Manhattan’s West Village open now through September 30th.

The museum showcases the ineffectiveness of Broken Windows policing, which has turned neighborhoods into occupation zones, torn apart families in communities of color, and hyper-criminalized minor offenses like jumping turnstiles or smoking marijuana.

The theory of Broken Windows policing assumes that if minor crimes are allowed to happen in a neighborhood without recourse, and signs of neglect like literal broken windows are visible, then it will lead to more disorder and eventually to serious crime. But in practice in New York, the theory has been used as a cover for discriminatory policing and harassment of communities of color.

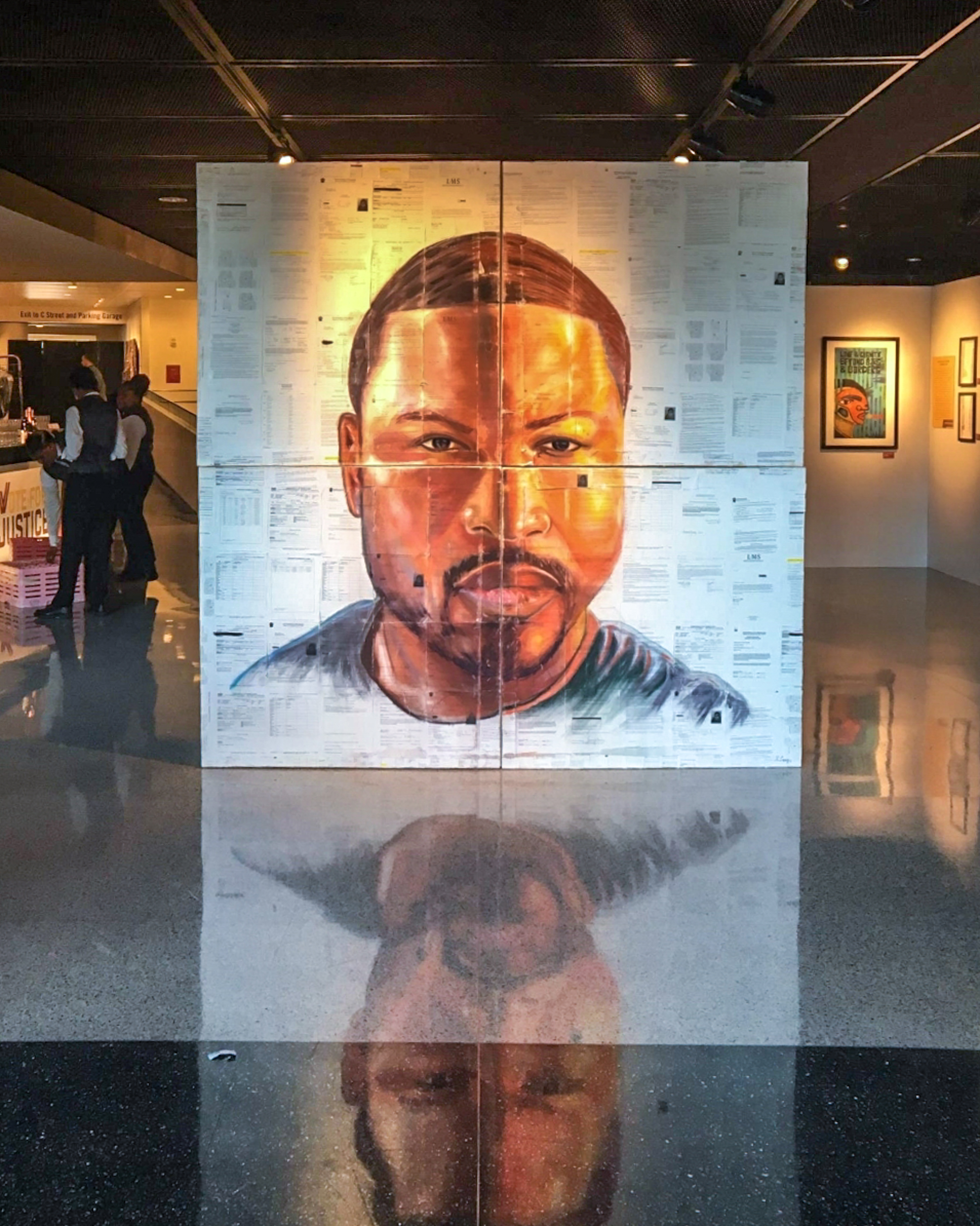

Philadelphia-based Russell Craig is one of the artists whose work is featured in the museum. Craig’s artistic style and stirring portraiture, which has been displayed nationally and internationally, were developed during his seven years in prison for non-violent drug offenses.

He said his self-portrait painted on his court documents from his time behind bars reasserts himself as an artist and an individual who refuses to be defined by systems of power. The piece is on display at the museum.

Our interview with Craig is condensed and edited for clarity.

I did some time inside Graterford [State Correctional Institution] and when I was inside I made a decision that I was going to be an artist when I was released. So when I was inside, I just practiced art. I went to the library and read books about art and gained some knowledge by practicing and learning to do portraits from a mentor. That’s how I got started.

As a young guy I was always interested in art. I was a foster kid and I used art as a way to escape into my own world— art was my escape and my focus. And it still is.

One of the pieces is a piece that got a lot of attention a few years ago at the Democratic National Convention. It’s my self-portrait on my prison documents.

I’m also doing a piece on the “Hip Hop Police.” I was very young when this problem was first brought to my attention. I was probably around 12, and I’m 37 now so it was a long time ago. I didn’t even think “Hip Hop Police” was real. I thought it was about cops that were sweating about rappers, but not like an official group, a real thing. So I did a little research because I wanted to put together a piece about how the police have surveilled artists and harassed artists. I tried to find any documentation or images about rappers who were being harassed by cops. The thing is, you don’t even have to be a criminal for the cops to watch you. It’s just that if you’re Black and successful, they’re pursuing you. Especially if you come from poverty.

I use those materials because they speak to and get deeper into the issue. It’s like a voice I hear— my “creative voice” I call it. All of my thoughts about art are louder than my regular thoughts, and they come out of nowhere sometimes… For the Eric Garner painting, I heard in my head “Go get the cigarettes off the street. Don’t buy them, go pick them up off of the street because Eric Garner died in the street. So go walk the streets and pick them up off the ground.” So that’s what I did.

I want them to realize our reality. People see what’s going on but they just go back to their normal, everyday lives. We’re becoming numb to a lot of misdeeds and crazy stuff that’s happening. I want my art to sit with people and I want them to entertain their thoughts about how crazy things are, especially when day after day after day we see the extremes of white supremacy within the police. It’s a continuous, undeniable thing: white police killing Black people. Why does this keep happening? I want them to see that it’s a kind of system.

Because it’s unpredictable as far as what can happen after you create something. You can reach some people, whereas other people might not even get it. And that’s a good thing. You can take one idea and the possibilities of creating something about that idea are endless.