NYCLU on Arrests of Pro-Palestine Protestors at NYU

Civil Liberties Union

The number of student suspensions in New York City public schools spiked dramatically over the past decade while the length of suspensions grew longer – a phenomenon disproportionally affecting black students and students with disabilities, according to a report released today by the New York Civil Liberties Union and the Student Safety Coalition that analyzes 10 years of previously undisclosed suspension data.

“Education is a child’s right, not a reward for good behavior,” NYCLU Executive Director Donna Lieberman said. “Sadly, the growing reliance on suspensions in New York City schools all too often denies children – often the most vulnerable and in need of support – their right to an education. This harsh approach to discipline, combined with aggressive policing in schools, pushes kids from the classroom into the criminal justice system.”

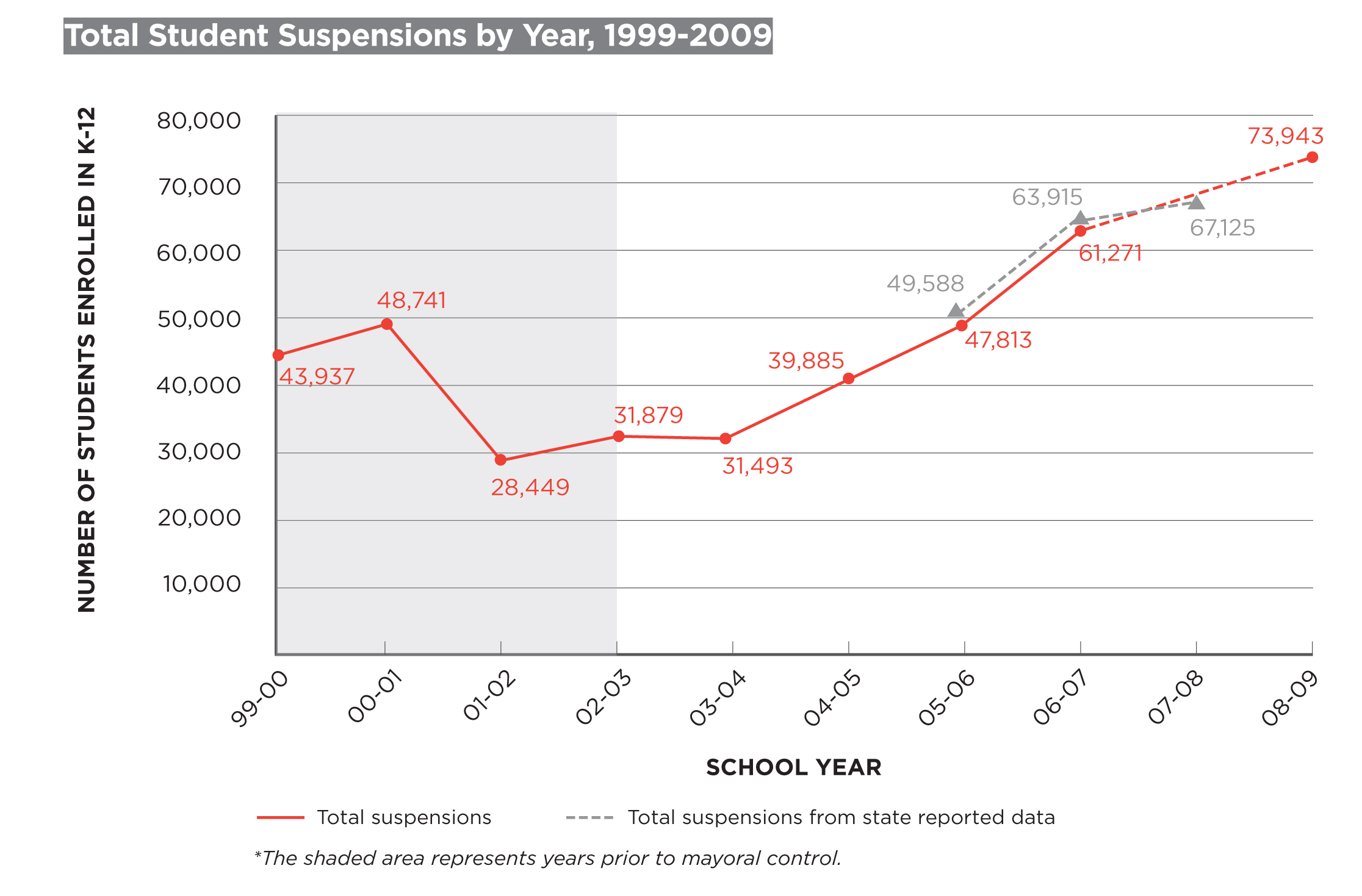

The report, Education Interrupted: The Growing Use of Suspensions in New York City’s Public Schools, analyzes 449,513 suspensions served by New York City students from 1999 to 2009.

The NYCLU and Student Safety Coalition obtained the raw data for the report through a series of Freedom of Information law requests to the New York City Department of Education (DOE) in 2008 and 2009. Statisticians and academics at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University processed and analyzed the data for more than a year.

According to the data, the number of suspensions served each school year nearly doubled over the decade – even though the student population has decreased over the same period.

Among the report’s findings:

The report partially attributes the rise in suspensions to the DOE’s Discipline Code – the code of conduct for the city schools that catalogues infractions and the acceptable range of disciplinary responses for each one. From 1999 to 2010, the number of behaviors for which a student must be suspended grew by 200 percent.

“If you increase the number of infractions that must draw a suspension, then more children are going to be suspended,” said NYCLU Public Policy Counsel Johanna Miller, the report’s primary author. “We encourage the DOE to continue recent steps to emphasize the need for non-punitive responses like peer mediation, guidance counseling, conflict resolution, community service and mentoring. These methods are proven to effectively address disciplinary issues while providing students valuable support and encouragement.”

Research has repeatedly demonstrated that overuse of suspensions can worsen school climate and is linked to lower test scores. Studies also show that students who are suspended tend to be suspended repeatedly, until they either drop out or are pushed out of school. A study of secondary school students, published in the Journal of School Psychology, showed that students who were suspended were 26 percent more likely to be involved with the legal system than their peers.

“The increasing and disproportionate use of suspensions in New York City schools negatively impact the school environment and drive down student achievement,” said Udi Ofer, NYCLU advocacy director and co-author of the report. “The Bloomberg administration must end its zero tolerance approach to school discipline and instead provide resources to schools to address the emotional and mental needs of children.”

The overuse of suspensions combines with heavy-handed street policing tactics used in too many of the city’s schools to push students from classrooms into the criminal justice system. School safety officers, NYPD personnel assigned to the schools, have become increasingly involved in maintaining school discipline. Students, some as young as five, have been handcuffed, taken to jail, and ordered to appear in court for infractions such as writing on a desk or talking back.

While school safety officers do not have the power to suspend students, they are often complaining witnesses at suspension proceedings, and are usually involved when disciplinary infractions are treated as criminal offenses.

The report offers the following recommendations to the DOE and state and city lawmakers: