Pro-Palestinian Campus Protests Shouldn’t be Snuffed Out by Police

Civil Liberties Union

Some of the same mistakes that plagued the government response to COVID have reared their ugly heads in the effort to deal with MPV.

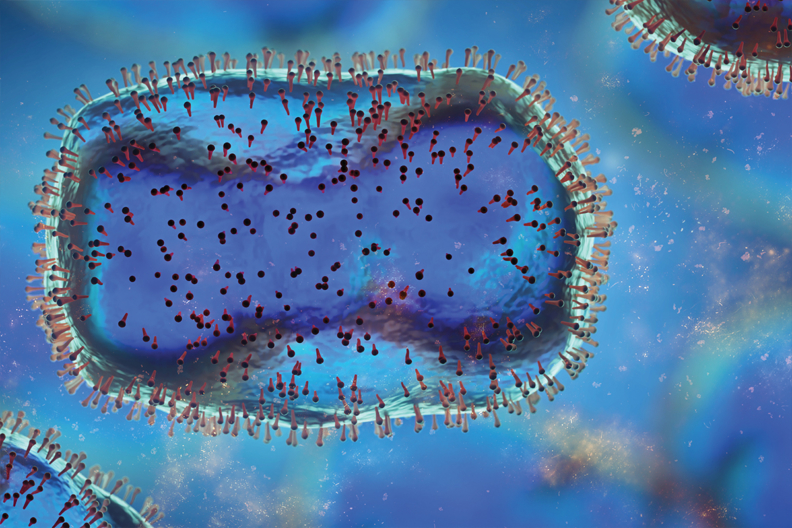

The spread of monkeypox/MPV across the country and particularly in New York City is stirring unwanted feelings of deja vu.

After two-plus years of the pandemic, some of the same mistakes, pitfalls, and shortcomings that plagued the government response to COVID have reared their ugly heads in the effort to deal with MPV. While anyone can contract MPV, it has been disproportionately impacting men who have sex with men. And worrying developments – like Rikers staff contracting the disease and potentially exposing people who are incarcerated – raise fears that other vulnerable populations could be especially impacted.

While policymakers have corrected some early mistakes in the MPV vaccine rollout, current plans raise concerns for the most impacted communities. New York still has the opportunity to learn the hard-fought lessons from the COVID response and to ensure the MPV rollout reaches those most in need. But that all depends on what policymakers and public officials do next.

In late June, New York City became the first city to expand eligibility for the MPV vaccine beyond those exposed to the disease. But the City’s initial response favored whiter and wealthier New Yorkers, as the Washington Post reported:

[T]he approach . . . favor[ed] the privileged who were able to wait in line for hours in the middle of the workday on the first day shots became available at a clinic in Chelsea, an upscale historically gay neighborhood in Manhattan, or spend[] hours on overloaded websites and on hold with clinics trying to book an appointment.]

Even when the City opened up appointments in Harlem, the majority of people who flocked to those slots were white and lived elsewhere; neighborhood residents were not permitted to walk in and receive vaccines. As a result, while Black New Yorkers make up 31 percent of the population most at risk for MPV, they have received only 12 percent of the vaccine doses administered.

Sound familiar? Barely a year and a half ago, New York’s COVID distribution plan required New Yorkers to spend hours on their computers hunting for quickly disappearing appointments, and white New Yorkers flocked to Washington Heights, crowding out locals for vaccination slots when clinics also did not accept walk-ins. The millions of people in our state who couldn’t sit by a computer all day were largely shut out of appointments, and they were more likely to be lower-income New Yorkers of color.

Since the initial vaccine rollout, the City has begun to work with community-based health centers, both to fill appointments at City vaccination sites and to provide vaccines directly to their patients.

To the City’s credit, it has expanded beyond the community-based health centers that it typically works with and allowed all community-based health centers in the City to apply, recognizing that community-based health centers are trusted providers who know how to meet their communities where they are and reach those most in need.

The federal government has struggled mightily to secure enough vaccine supply to take on the public health emergency. Earlier this month, the Food and Drug Administration announced plans to stretch the current supply by authorizing an alternative method of administration in which the vaccine is administered intradermally, or between layers of skin, rather than below the skin, as vaccines are typically administered. This requires less of the vaccine to be used, dramatically increasing the supply.

But, there is only one study from 2015 demonstrating the efficacy of intradermal MPV vaccine administration, and some public health experts have expressed concerns about the lack of evidence proving the effectiveness of this method of administration. Compounding the problem, intradermal vaccine administration is notoriously tricky, and many health care providers are not trained in the technique. Intradermal vaccine administration is also more likely to cause keloids or raised scars.

Intradermal administration – if effective – could stretch the number of vaccine doses available and protect more people from MPV. But there is also a risk that people who were largely locked out of the City’s initial vaccine rollout, like many Black New Yorkers, may fear they’re getting a less effective vaccine.

Black communities are already disproportionately likely to be alienated from and distrustful of our health care system as a result of the racial biases that pervade that system. So the perception that Black New Yorkers are being offered an inferior vaccine – whether or not it is true – may feed vaccine hesitancy.

There are other reasons to believe there could be significant vaccine hesitancy. Currently, only some people are eligible for MPV vaccines: gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men, as well as transgender, gender non-conforming and non-binary people, who have had “multiple or anonymous sex partners in the last 14 days.” Because of this, there is good reason to believe some may avoid vaccination if they fear an intradermal vaccine will leave a mark on their arm that could out them.

First, New York must increase the number of people who qualify for the vaccine, as New Jersey recently did. Those newly eligible should include people whose jobs put them at higher risk of contracting the disease, including health care workers, massage therapists, and sex workers. This will reduce any stigma that may be associated with receiving a vaccine and will also slow down and stop the spread of MPV.

Second, vaccine confidentiality is a critical piece of any plan to tackle the spread of MPV. There is a bill awaiting Gov. Hochul’s signature that would ensure the information people share to make a vaccine appointment, as well as information in New York State’s vaccine registry, is kept confidential. The bill would also make clear that vaccine information cannot be used to criminalize or deport anybody.

This is particularly important since Gov. Hochul has required that all MPV vaccine recipients be included in the State’s vaccine registry. It’s also critical because some men who have sex with men or trans people may be wary of receiving an MPV vaccination if they fear being outed. You can urge Gov. Hochul to sign the vaccine confidentiality bill here.

Finally, New York must continue to work with community-based health centers, organizations, leaders, and activists who best know how to reach their constituents.

If MPV is not contained, it could spread rapidly, and it’s important to remember that anyone can contract the disease. MPV can be successfully curtailed, but it won’t happen through sheer luck. Public officials’ response must prioritize the most vulnerable and affected New Yorkers — taking the right steps to protect these communities will help protect us all.