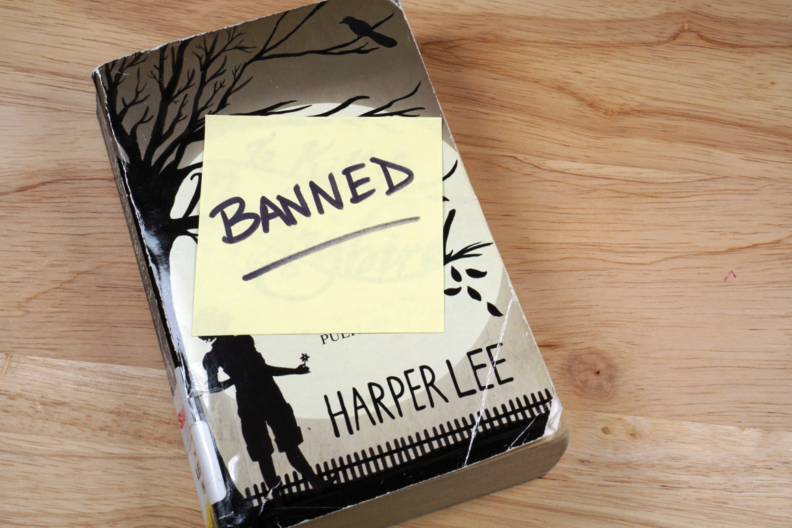

NY Schools are Banning Books. Here’s What You Can Do About it

We must make sure school libraries remain vibrant, inclusive spaces for all students.

A scene from Long Island: Three school board members return from a parent convention with a list of “objectionable” books. They search the catalog and realize that nine are in school libraries in the district. They direct a committee to review the books and recommend whether they should stay on shelves. When the committee decides to keep virtually all the books, the board votes to remove them anyway, stating that the titles are “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy.”

Sound like recent events? In fact, the school board in the Island Trees Union Free School District removed the books – including Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut and Black Boy by Richard Wright – in 1976. The NYCLU sued and fought the case all the way to the Supreme Court, where a plurality of the justices concluded that school districts cannot ban books with the intent of imposing a narrow orthodoxy of viewpoints and values. Today, the case remains the only time the Supreme Court has addressed the issue of censorship in school libraries.

Almost fifty years later, a new generation of activists set on purging school libraries have driven book banning to an all-time high. In the first six months of the 2022-2023 school year alone, PEN America documented 1,477 book banning incidents. Thirty percent of the books challenged are about race or racism or feature people of color, while more than one in four include LGBTQIA+ characters or themes.

These censorship attempts happen close to home, not just in red states. A Journal News investigation found that more than 200 complaints were filed in Hudson Valley school districts alone between 2020 and 2022.

Wappingers Central School District removed Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe and Briarcliff Manor Union Free School District censored Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda by J.P. Stassen in response to challenges. Recently, the School Board in the Clyde-Savannah Central School District removed and then restored five books, including All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, to the district’s libraries after two staff members appealed the decision to the Commissioner of Education.

School districts that remove LGBTQIA+ and Black and Brown voices from library collections may violate the First Amendment. But they could also violate schools’ legal and ethical duty to cultivate a safe and supportive learning environment for all students. Given the importance of the rights at stake, school districts should have clear policies for handling challenges to library and curriculum materials fairly and efficiently. After all, we are talking about students’ right to learn.

Yet, many districts have no policies in place and the ones that do exist are often vague and lack necessary safeguards. The NYCLU designed a model policy with these districts in mind. We used the New York State School Board Association’s template policies as a starting point, incorporating guidelines developed by the American Library Association and strong provisions from other district policies.

The policy advocates for the creation of a district-wide committee, including an administrator, a librarian, two teachers, a reading or other content specialist, two parents, and two high school students, to review challenges to curricular and library materials. The committee makes a recommendation to the school board on whether to retain or remove the book, and the board votes to adopt or reject the committee’s recommendation.

These censorship attempts happen close to home, not just in red states.

Two features of the model policy are particularly important:

First, the policy forbids removal of materials before the review process is complete.

Without explicit guidance, school staff may feel pressure to pull books off shelves as soon as a complaint is filed. Doing so denies students access to a book without any assessment of whether the complaint is valid simply because the school wants to avoid conflict. Silencing someone because of concern about how others will react is called a “heckler’s veto” and it is forbidden by the First Amendment.

Second, the policy is designed to honor the professional judgment of educators.

Librarians are trained to curate wide-ranging collections of materials for students and are bound by a code of ethics which includes a commitment to intellectual freedom and racial and social justice.

Our model policy identifies librarians as the key decision makers responsible for selecting library materials and provides that books should only be removed if they lack any educational purpose as defined by the district’s library selection guidelines.

Even if a material is removed, the model policy states that the decision should not be understood as a “judgment of irresponsibility” on the part of the educator or librarian who selected it. One of the most troubling consequences of book challenges is that educators, fearing controversy, may avoid assigning or selecting books that feature the voices and experiences of marginalized people. At a time when educators and librarians are being explicitly targeted by activists, it is critical to provide protection so that they can continue providing students with the diverse, inclusive materials students need and deserve.

The New York Legislature is also wrestling with the question of how to stop book bans and is currently considering four bills that would require the creation of new policies.

The first, the Freedom to Read Act, would require the Commissioner of Education and library systems to develop policies to empower library staff to “curate and develop collections that provide students with access to the widest array of developmentally appropriate materials available.”

The other three bills are modeled on a law recently passed in Illinois. That law requires local libraries that receive public funding to adopt the American Library Association’s Library Bill of Rights or alternately to develop “a written statement prohibiting the practice of banning books or other materials.” Our model policy would comply with either approach.

We must make sure school libraries remain vibrant, inclusive spaces for all students. Thankfully, Gov. Hochul seems to agree. As she said back in June, “[e]veryone – and particularly our state’s young people – deserves to feel welcome at the library.”

Want to take action? Share the model policy with your local school board using the template letter. Spread the word using the one-pager. And if you believe that a book has been removed inappropriately from your school’s curriculum or library, contact the NYCLU at schools@nyclu.org.