Pro-Palestinian Campus Protests Shouldn’t be Snuffed Out by Police

Civil Liberties Union

Elbridge Gerry was vice president of the United States under President James Madison. He is not widely remembered for that achievement.

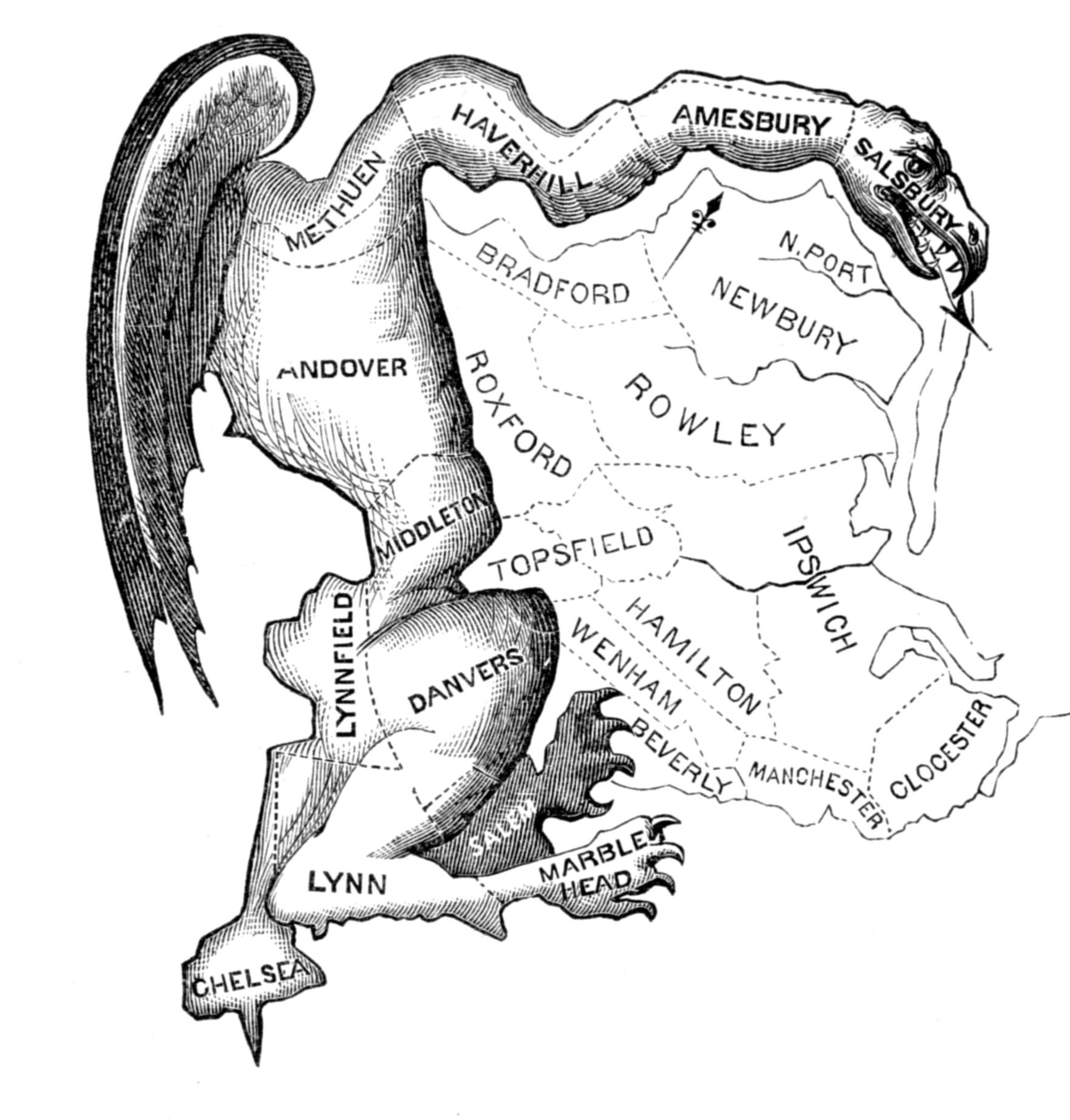

He is more commonly identified, if recalled at all, for his role as governor of Massachusetts and his approval of a legislative districting plan that advantaged his partisan allies by creating irregularly contoured districts – including one shaped like a salamander.

The salamander-like district was ridiculed in a contemporary political cartoon as a “gerrymander.” And with that, political gerrymandering has come to be understood as the practice of drawing legislative district lines intended to skew the outcome of future elections for partisan advantage or for the protection of incumbents.

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral argument in a case challenging the constitutionality of this practice. In the last four decades, the Court has fully considered only three other challenges to political gerrymanders, and each time the Court stopped short of finding the practice unconstitutional. The Court expressed concerns about such manipulative practices, but was unable to identify manageable standards for distinguishing between permissible and impermissible legislative line-drawing. The Court seemed to believe that the standards previously proposed by those challenging the gerrymandered districts were mathematically-based and too complicated for courts to apply.

But, as the ACLU/NYCLU’s amicus filing in today’s Supreme Court challenge shows, such standards need not be analytically complicated.

State legislatures violate this neutrality principle when their primary motive is to draw district lines to secure a partisan advantage or to protect incumbents.

Here is the reason why. Suppose a state legislature were to direct election officials to rig all voting machines in the state to manipulate the outcome of elections. We would all understand that such behavior is wrong. Yet, drawing legislative district lines for partisan or political advantage is not much different. In both circumstances, a state legislature engaged in such practices would be violating the government’s obligation to remain neutral in its administration of elections.

There is a constitutional basis for this obligation of neutrality. The Court has rendered a series of First Amendment decisions holding that when the government regulates expressive activities within public parks or other public facilities, it may not privilege some speakers over others based upon the viewpoints expressed or the political affiliation of the speakers. As Justice Thurgood Marshall observed: “There is an equality of status in the field of ideas and government must afford all points of view on equal opportunity to be heard.” This equal opportunity must also be extended to voters entering the polling place to engage in political expression in support of candidates and must be enforced by imposing an obligation of government neutrality.

These past decisions of the Supreme Court, which lie at the crossroads of the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, provide significant support for the principle that the government must remain neutral in administering elections and that it cannot have its thumb on the electoral scale.

These cases suggest a straightforward standard for resolving challenges to gerrymandered districts which turns first and foremost on the motivation of those who create the districting arrangement. State legislatures violate neutrality principles when their primary motive is to draw district lines to secure a partisan advantage or to protect incumbents and when they accomplish their impermissible goals.

Elbridge Gerry participated in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. But he ultimately opposed ratification of the Constitution because it contained no Bill of Rights to protect free expression and other fundamental liberties. His objection was, of course, subsequently addressed. We now have a First Amendment that protects free expression, including expression undertaken in the voting process.

Given Gerry’s insistence on a Bill of Rights, it would be supremely ironic if the Court were to now invoke the First Amendment to invalidate political gerrymandering.

It would also be the right thing to do.