NEW YORK – The length of time immigrant children are detained in government custody is growing dramatically due to new requirements for fingerprinting and an enormous resulting backlog, according to a national class action lawsuit filed today by the New York Civil Liberties Union, American Civil Liberties Union, National Center for Youth Law, and the law firm Morrison & Foerster. Delays in releasing children have contributed to the total number of migrant children in government custody ballooning to its highest level in history.

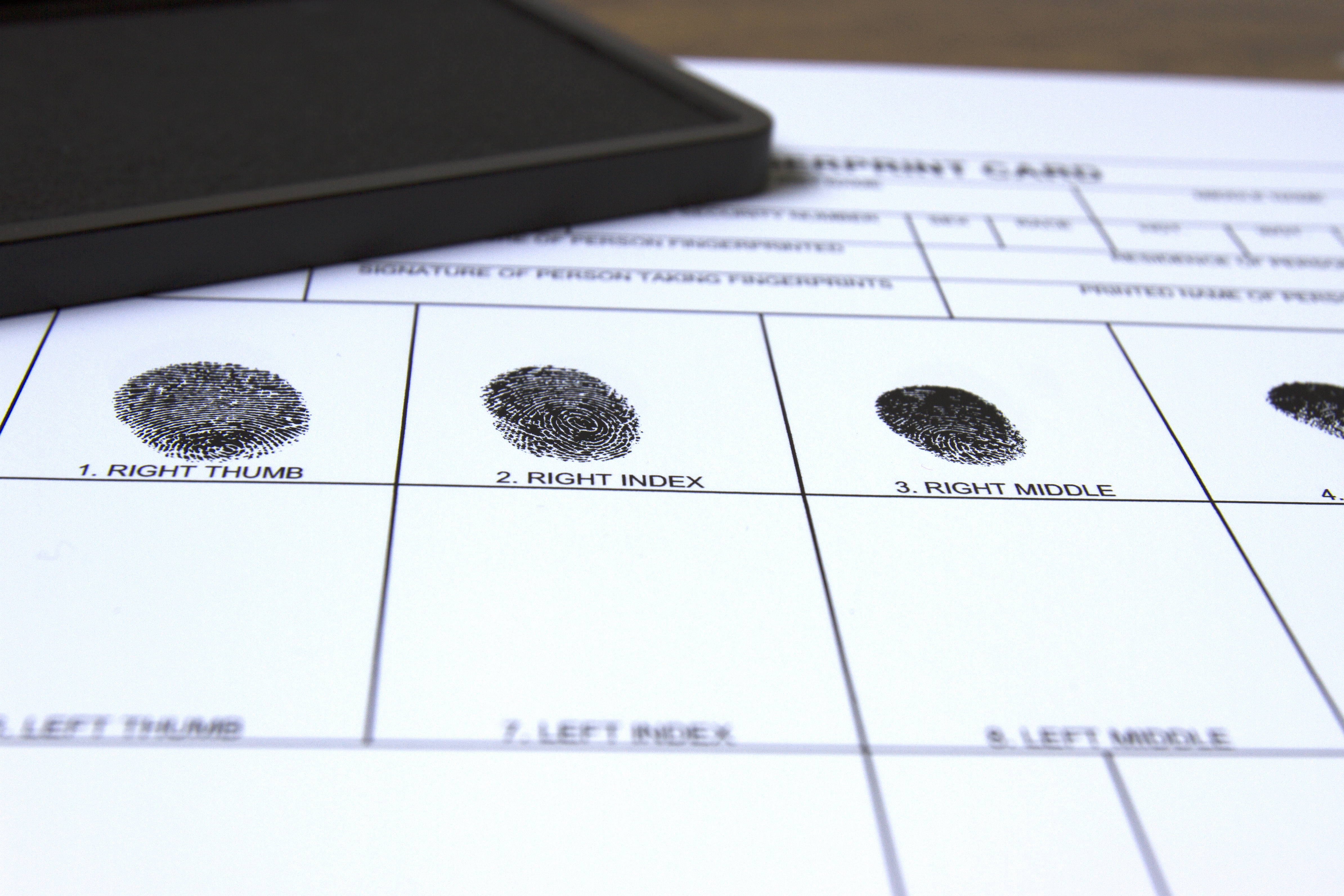

The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), the federal agency responsible for immigrant children in government custody, began requiring fingerprint checks of children’s parents and all of their household members in June 2018, shortly after adopting new policies to share fingerprints with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for enforcement purposes. Fingerprint-based background checks now add weeks and months to the length of time migrant children are detained. Family members must wait weeks for appointments to have their fingerprints taken at one of the limited sites ORR has set up, and then wait weeks longer – and in some cases months longer – for results to be processed.

“The new fingerprint policy has kept children detained for long periods away from their parents and exposed their family members to the risk of deportation,” said Paige Austin, NYCLU staff attorney. “The longer children are detained the more likely they are to suffer irreversible psychological harm, relive trauma, fall behind in school, and, for those who turn 18 in custody, risk being transferred to an adult facility facing deportation proceedings.”

Across the country, hundreds of children are detained in government custody while waiting for their parents’ or other sponsors’ background checks to be completed. In recent months, the NYCLU helped secure the release of two children whose parents each waited more than six weeks for their fingerprints to be processed. The quick release of both children once legal action was taken or threatened highlighted the fact that parent fingerprints can be processed quickly.

“The children that come here are not coming for fun, they’re running from abuse or abandonment or crime. This policy is destabilizing children’s lives, including my daughter’s,” said Norma Duchitanga, whose daughter is detained at the Nueva Esperanza Southwest Keys shelter in Brownsville, Texas. “Children are losing time in school, being re-traumatized and living in fear. All of this will stay with them for the rest of their lives. I want my daughter home with me because not only is it going to be good for her, but I know she’ll be able to contribute to and do good for this country. All I ask is that there is justice for these children and that the government do what is right.”

Today’s suit names six children in government custody who have been waiting between two weeks and nearly four months for the results of their sponsors’ fingerprint background checks. Two Guatemalan sisters, aged 14 and 16, detained at Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry, New York, have been waiting nearly four months for their father’s fingerprints to be processed. Brothers E.S.O., 16, and O.S.O., 11, have been detained at Cayuga Center in Manhattan, waiting since July for their mother’s fingerprint results. The sister of a 15-year-old boy detained in Crittenton, California submitted her fingerprints in August, and again in October, yet is still awaiting results. Duchitanga submitted her prints over two weeks ago, and is anxiously awaiting the results because she fears that her 17-year-old daughter will be transferred to an adult facility and deported after she turns 18 next month.

“These children are languishing in custody because of administrative problems that are entirely the government’s own fault. The Trump administration should stop making kids suffer and promptly fix the mess it has created,” said Stephen Kang, an attorney with the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project.

Prior to ORR’s new policy, only non-parent relatives and non-relatives seeking to sponsor children in ORR custody were required to submit fingerprints for background checks. Household members did not need to be fingerprinted unless there was a special concern for the safety of a child. Because more than 40 percent of children in ORR custody are released to a parent, the June 2018 changes have hugely increased the number of people who have to be fingerprinted, but ORR has not taken the necessary steps to ensure that fingerprinting can occur in a timely fashion.

This lawsuit seeks to represent a class of more than one thousand children in government custody whose release is contingent on the fingerprint-based background check of their sponsor or the sponsor’s household members. The length of time that children spend in government custody has spiked precipitously in recent months, leading to overcrowded shelters. To accommodate the swelling population, the agency is now transferring hundreds of children, many of whose releases are pending the results of fingerprint checks, from shelters around the country to a “tent city” in the Texas desert that is not licensed by state child welfare authorities.

In April 2018, ORR also agreed to share the identities and fingerprints of children’s parents and other proposed sponsors and household members with ICE and Customs and Border Patrol (CBP). In May, ICE issued regulations allowing the agency to use the information ORR provides about sponsors for immigration enforcement. These changes in policy have allowed ORR and ICE to work together to turn the process for safely releasing kids in immigration custody to family members into a tool for immigration enforcement. In September, an ICE official testified to Congress that at least 41 people have been detained by ICE as a result of applying to sponsor children in ORR custody.

“The Trump administration’s new fingerprint requirements have had the predictable and unconscionable effect of keeping children locked up for months, even though their families are ready and desperate to care for them,” said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union. “The Trump regime is using children to entrap family members in its deportation dragnet.”

The lawsuit argues that ORR’s new fingerprinting requirements violate the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, a federal statute that mandates the prompt release of children from immigrant detention, and violates due process rights and the Administrative Procedure Act.

“For more than 20 years there was agreement that detaining immigrant children is harmful, and the government should release them as quickly as possible. The Trump administration has chosen to do the opposite,” said Leecia Welch, senior attorney at NCYL and co-counsel in the Flores case. “A simple process that should take days now takes months due to the administration’s inept and unlawful policies and practices. There is a simple solution to this Trump administration-created crisis, and we are hopeful that our litigation will result in a quick resolution that promptly reunites detained children with their families.”

The case, Duchitanga v. Lloyd, was filed in federal court in the Southern District of New York.

“It is absolutely vital to limit the time children are separated from their families as much as possible during what can be a traumatic process,” said Morrison & Foerster partner Michael Birnbaum. “Morrison & Foerster is proud to stand alongside the NYCLU, ACLU, and NCYL as we continue our advocacy on behalf of migrant children.”

In addition to Austin, NYCLU staff on the case include associate legal director Christopher Dunn, staff attorney Robert Hodgson, investigator Paula Garcia Salazar, legal fellow Victoria Roeck and paralegal Ingrid Sydenstricker. NCYL staff on the case also includes attorney Neha Desai, director of immigration, and attorney Melissa Adamson. The Morrison & Foerster team led by New York litigation partner Birnbaum also includes associates Elnaz Zarrini and Lauren Gambier and senior pro bono counsel Jennifer Brown.