Testimony Before the Joint Legislative Budget Hearing on Health

Civil Liberties Union

My name is Robert Perry. I am the legislative director of the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU). The NYCLU, a state affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union, has approximately 50,000 members. The NYCLU is devoted to the protection and enhancement of those fundamental rights and constitutional principles embodied in the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution and the Constitution of the State of New York. Central to this mission is our advocacy regarding fairness and equality in the state’s criminal justice system.

The legislature’s announcement of this hearing appears to acknowledge the broad and growing consensus among policy experts, criminal justice scholars, and law makers that the “war on drugs,” with its singular emphasis on incarceration, has failed. It was in 1999 that federal drug czar General Barry F. McCaffrey stated, “We can’t incarcerate our way out of [the drug] problem.”

Many prominent New Yorkers who were early supporters of the harsh penalties prescribed by the Rockefeller Drug Laws have renounced their support for those laws. John Dunne, the former Republican senator and original sponsor of the Rockefeller Drug Laws, has said, “The Rockefeller Drug Laws have failed to achieve their goals. Instead they have handcuffed our judges, filled our prisons to dangerously overcrowded conditions, and denied sufficient drug treatment alternatives to nonviolent addicted offenders who need help.” The late Thomas A. Coughlin, III, who for fifteen years served as the state’s Corrections Commissioner, concluded that under the drug laws the state was “locking up the wrong people for the wrong reasons.”

Other critics have deplored the grave collateral consequences of the state’s harsh mandatory sentencing scheme — particularly for the low-income inner city communities of color that have been the primary focus of drug-law enforcement. In an article published recently in The Boston Review, the African American scholar Glenn C. Loury, a noted social conservative, called the war on drugs a “monstrous social machine that is grinding poor black communities to dust.”

We urge you, as legislative leaders, to advance the critique of a sentencing structure that ties the hands of judges, grants prosecutors enormous and essentially unreviewable powers, and results in the routine miscarriage of justice. I respectfully submit that in order to pursue this inquiry the legislature must address the stark racial and ethnic disparities in the population incarcerated for drug offenses; the impact of drug-sentencing laws on the integrity of the criminal justice system; the relationship between rates of incarceration and crime rates as regards drug offenses; and the social and economic consequences of the high incarceration rates for drug offenses.

It is well documented that there are gross racial and ethnic disparities in New York State’s prison population, particularly among those incarcerated for drug offenses. There is also voluminous evidence demonstrating the causes of these disparities, including selective arrest and prosecution, inadequate legal representation, and the absence of judicial discretion in the sentencing process.

It is not possible to evaluate New York’s sentencing laws without analyzing the ways in which race enters into law enforcement and judicial procedures. In considering what a reform of the state’s drug-sentencing laws would like, we urge that legislators and policy makers consider the following.

The racial disparity in New York’s prison population has increased dramatically since the mid-1980s and the advent of the “war on drugs.”

There were 886 persons incarcerated for drug offenses in 1980. Of these individuals, 32 percent were Caucasian; 38 percent were African American; and 29 percent were Latino. In 1992, the year in which the state reported the highest number of commitments for drug offenses, 5 percent of those incarcerated were Caucasian; 50 percent were African American; and 44 percent were Latino.

The demographics of the inmate population serving time for drug offenses in 2000 had changed little from the data reported in 1992. (See table below.) Of the 8, 227 new commitments for drug offenses in 2000, 6 percent were Caucasian; 53 percent were African American; and 40 percent were Latino. The disparities persist. Today more than 90 percent of persons incarcerated for drug offenses are African American or Latino.

|

The racial and ethnic disparities among the population incarcerated for drug offenses in New York State do not reflect higher rates of offending among African Americans and Latinos.

In a relatively recent government study, a total of 1.8 million adults in New York (about 13 percent of the total adult population) reported using illegal drugs in the preceding year. Of those reported users of illicit drugs, 1.3 million – or 72 percent — were white.

Moreover, research indicates that whites are the principal purveyors of drugs in the state. When the National Institute of Justice surveyed a sample of more than 2,000 recently arrested drug users from several large cities, including Manhattan, the researchers learned that “respondents were most likely to report using a main source who was of their own racial or ethnic background regardless of the drug considered.” Upon closer analysis these findings reveal that there are, indeed, many more drug sales in white communities than there are in communities of color, but the transactions that occur in white communities tend to escape detection because they take place behind closed doors in homes and offices.

Criminologist Alfred Blumstein, the nation’s leading expert on racial disparities in criminal sentencing practices, has concluded that with respect to drug offenses, the much higher arrest and conviction rates for blacks are not related to higher levels of criminal offending, but can only be explained by other factors, including racial bias.

The over-representation of African Americans and Latinos in New York’s prison population is the consequence of unequal treatment at each stage of the criminal justice process.

Arrest: It has been widely documented that the war on drugs has been waged largely in poor, inner-city communities. Noted sociologist Michael Tonry explains: “The institutional character of urban police departments led to a tactical focus on disadvantaged minority neighborhoods. For a variety of reasons it is easier to make arrests in socially disorganized neighborhoods, as contrasted with urban blue-collar and urban or suburban white-collar neighborhoods.”

New York City’s policing practices demonstrate the routine and widespread practice of racial profiling. According to data recently released by the NYPD, police officers conducted 508,540 stop and frisks in 2006. Fifty-five percent of those stop encounters involved blacks, 30 percent involved Latinos, and only 11 percent involved whites. Those percentages bear little relation to the demographic profile of the City’s overall population. But the most salient fact is that 90 percent of the persons stopped were found to have engaged in no unlawful activity.

Racial bias is starkly evident in New York City’s marijuana arrest statistics. Although whites use marijuana at least as often as blacks, the per capita arrest rate of blacks for marijuana offenses between 1976 and 2006 was nearly eight times that of whites. During this period there were 362,000 marijuana possession arrests in New York City. Fifty-four percent of those arrested were black and 30 percent were Latino; only 14 percent of the arrestees were white.

• Prosecution: The plea bargaining process is largely hidden from public scrutiny; but even assuming prosecutors in New York are making completely race-neutral charging and plea-bargaining decisions, there are other factors that place black and Hispanic defendants in legal jeopardy. Chief among them is the fact of unequal access to legal resources. Most persons charged with drug crimes are poor and must rely upon the state’s public defense system—which is in a state of crisis, according to a recent report by the Commission on the Future of Indigent Defense Services.

The Commission’s report concludes that, “Whereas minorities comprise a disproportionate share of indigent defendants and inmates in parts of New York State, minorities disproportionately suffer the consequences of an indigent defense system in crisis, including inadequate resources, sub-standard client contact, unfair prosecutorial policies, and collateral consequences of convictions.”

• Sentencing: By the time a drug case reaches the sentencing stage the die has been cast. The racial inequities that operate in each phase of the criminal justice system produce a pool of defendants comprised almost exclusively of poor people of color. Ninety-eight percent of those defendants will enter a guilty plea for which the judge will be required to impose the mandatory minimum sentence.

Over the years, many judges have expressed frustration and outrage at the mandatory minimum sentences prescribed by the Rockefeller Drug Laws:

“I sentence the defendant with a great deal of reluctance . . . and will state I think it’s an inappropriate sentence and an outrageous one for what was done in this case.” Judge Florence M. Kelly, Supreme Court, New York County

“When I say the law is draconian, in your case it is. I am required by law to impose a sentence that in my view you don’t deserve.” Judge Martin E. Smith, Supreme Court, Broome County

“But the bottom line is that I am handcuffed as a matter of law, so I have to do what the law says I have to do, because I cannot violate the law. But I am not going to give your client more than the minimum sentence.” Judge Seymour Rotker, Supreme Court, Queens County

We aspire to fairness in our system of criminal justice – due process of law, equal protection under law. We seek to enforce these principles not only through procedural checks and balances, but also by ensuring vigorous advocacy – on behalf of the people and of the defendant – subject to the authority of a neutral arbiter: the judge.

With the enactment of the Rockefeller Drug Laws the state of New York elected to subvert judicial fairness – and to subvert the constitutional right to a fair trial; to a zealous defense; and, if found guilty, to a sentence that is commensurate to the wrong committed. This subversion of the judicial process is a consequence of the harsh mandatory sentencing scheme that relegates the judge to the role of bystander in the courtroom.

As one prominent legal scholar explains:

Mandatory minimum sentences not only have stripped judges of sentencing power but also have driven defense attorneys to advise clients to accept plea bargains that they may previously have advised against. . . .

In cases involving mandatory minimum offenses, the stakes are often too high for a defendant to exercise his constitutional right to trial, regardless of the weakness of the prosecutor’s plea offer. Even if he believes he has a good chance of being acquitted because of the weakness of the government’s case or the strength of his own defense, the defendant can never be sure of what the verdict of a judge or jury will be. If the judge is permitted to exercise discretion when imposing sentence, the defendant has at least a chance of convincing the judge to show some leniency. However, if the defendant is convicted of one or more offenses, each of which requires a mandatory minimum term of incarceration, he faces a definite, long prison term.

The cases in which injustice has been worked by the state’s drug-sentencing laws are legion. I offer just three recent examples that illustrate the perverse outcomes mandated by the harsh and irrational character of these laws.

The case of Rupert B. Rupert B., twenty years old, lived with his mother, teenage sister, and girlfriend. He dropped out of school at seventeen to help support his family after his father left. However, without a high-school diploma or trade skills, he struggled to find work. His mother received public assistance, but had been falling behind on her rent. With his mother facing eviction, and his girl friend pregnant, Rupert accepted a job that he had attempted to avoid his entire life. He started selling drugs on the street corner, making enough in a few weeks to appease the landlord. But he was soon arrested, charged with selling a single vial of crack to an undercover officer. The judge gives him two choices: serve a one-year sentence (which meant leaving his family behind), followed by a year of post-release supervision, or participate in a twelve-to-eighteen-month drug program that he did not need – Rupert had never used drugs. Nevertheless, he accepted treatment. Not surprisingly, his progress reports were poor. He was accused of not participating fully in the program. Eventually, Rupert was offered a full-time job in New Jersey, which required him to spend the entire day out of the state. He accepted the job, even though it precluded him from finishing treatment. He was terminated from the program, returned to court on a warrant, and was sentenced to state prison.

The case of Hector V. Hector V., a Hispanic man of fifty-two, suffered from a physical disability. He had started using drugs when he was in his forties, after his wife left him. He had been using off and on since then. When he was forty-five, at the height of his addiction, Hector was so desperate for money to buy drugs that he broke into a neighbor’s house and stole some jewelry. He was caught on the fire escape and received a sentence of two to six years. He was forty-nine when released. Hector managed to stay clean for a while, but within a couple of years, began using again. Broke and unable to support his habit, he made a deal with a seller in his building. If anyone asked, Hector would escort the person to the seller’s apartment. In exchange, the seller would pay Hector in crack cocaine. When a haggard-looking man approached and asked Hector if he knew where to buy drugs, Hector escorted him to the seller’s door and observed the drug sale. Minutes later a team of undercover narcotics officers raced in and arrested Hector. The charge: acting in concert to sell drugs to an undercover officer. If Hector had been a first-time offender, he would have been eligible for treatment. But because of the robbery conviction, he was classified a violent felony offender. The sentencing laws required that he serve at least six years in prison.

The case of Ashley O’Donoghue: In 2003 O’Donoghue, a twenty-year-old African American from Manhattan with no criminal record, was arrested in Oneida County for selling drugs in a state police buy-and-bust operation. Ashley was a high-school drop out with a history of learning disabilities. He was charged with an A-I felony and faced a sentence of fifteen-years-to-life. The defendant and his parents felt he had no choice but to accept the plea offered by the prosecutor. In February 2004, Ashley O’Donoghue pleaded guilty and was sentenced to seven to twenty-one years in prison for a first-time nonviolent offense. His parents have become outspoken advocates on behalf of their son – and others who have become victims of the state’s irrational drug-sentencing laws.

In its preliminary report, issued in October 2007, the New York State Commission on Sentencing Reform stated the following:

The Commission heard many arguments on both sides of the debate as to whether to retain, eliminate or modify mandatory minimum sentences for certain first-time and repeat felony drug offenders. The Commission members heard forceful arguments from prosecutors that the mandatory minimum and second felony offender laws, including those for felony drug offenders, “played a vital role in providing us with the framework which has led to the tremendous and historic reduction in crime we have [seen] since about 1993.

The corollary to this argument, and one that is being made by some prosecutors, is that further reform of mandatory minimum sentences will cause the crime rate to rise again to the level of “the bad old days.” These arguments may be “forceful” – but they lack a sound empirical basis.

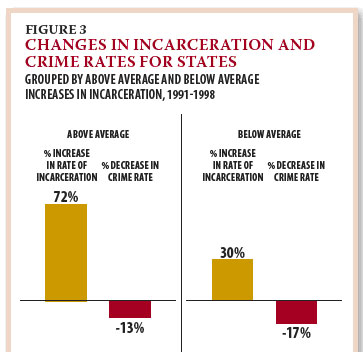

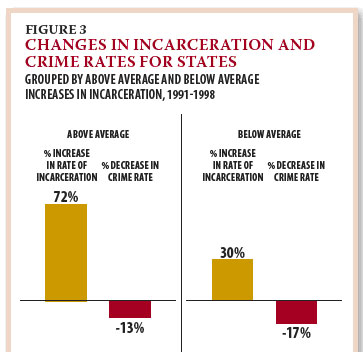

A recent study by the Sentencing Project examined prison and crime data and found that “there was no discernible pattern of states with higher rates of increase in incarceration experiencing more significant declines in crime.” Indeed, states that reported below-average increases in incarceration rates had above-average declines in crime rates. (See table below.)

Nevertheless, there are those who persist in advancing the argument that massive incarceration is a rational response to an urgent public safety problem; and that imprisoning large numbers of drug offenders has led to a reduction in crime. Professor Glen C. Loury challenges this thesis.

Increased incarceration does appear to have reduced crime somewhat. But by how much? Estimates of the 1990s reduction in violent crime that can be attributed to the prison boom range from 5 percent to 25 percent. Whatever the number, analysts of all political stripes now agree that we have long ago entered the zone of diminishing returns. The conservative scholar John DiIulio, who coined the term ‘super predator’ in the early 1990s, was by the end of that decade declaring in the Wall Street Journal that “Two Million Prisoners Are Enough.” But there was no political movement for getting America out of the mass-incarceration business. The throttle was stuck.

Indeed, there is research indicating that that the “concentration of incarceration” in particular communities “may actually elevate crime within neighborhoods.” Locking up people who break society’s rules presumes that their neighborhoods will be safer once such people are removed. But, “[t]he constant rearrangement of social networks through removal and return of prisoners” creates instability that leads to more, not less, disorder. This is because the role of formal social controls in maintaining law and order—the police, parole and probation officers, the courts, etc.—are only one piece, and probably the less critical piece, of the puzzle. More important are what social scientists call the “informal social controls” which regulate individual behavior in a community. “When places become unsafe, it is not primarily due to a breakdown in the formal social controls of the state, but because of the limitations of the informal social controls operating in those places. This is a routine sociological insight.”

The lesson from this research is clear: Intact families, churches, workplaces, social clubs, organized youth groups and civic associations have a greater positive impact on public safety than the police do. And all of those institutions are weakened when such large numbers of residents are either incarcerated or just returning from prison. `

Over the past twenty-five years, hundreds of thousands of poor, minority New Yorkers have been cycled in and out of the prison system. Drug offenders make up one-quarter of New York State’s prison population today. Most of them were identified, upon admission to prison, as drug abusers by the Department of Correctional Services. Most are repeat offenders.

A recent study of fifty typical ex-offenders, whose average age was forty-one, found they had spent, on average, of one-third of their lives in prison for non-violent, small-scale drug offenses. This speaks to a policy of failure – not one of success. What’s more, the collateral damage of the state’s drug laws is inestimable. New York’s drug-sentencing scheme has so damaged the state’s most vulnerable communities that policy-makers’ asserted commitment to fairness, justice and equality cannot be taken seriously. This damage has deeply corroded the social and economic networks that are essential to sustain communities.

Diminished opportunity for economic and life success: Prisoners and formerly incarcerated persons suffer extremely high unemployment rates. In New York, up to sixty percent of ex-offenders are unemployed one year after release. It is generally the case that for an incarcerated black man, wages earned after release from prison are 10 percent less than wages earned before incarceration.

According to Professor Loury, the ramifications of a black man’s serving time for a drug offense are even more dire than these statistics suggest. “While locked up, these felons are stigmatized – they are regarded as fit subjects for shaming. Their links to family are disrupted; their opportunities for work are diminished . . . . They suffer civic ex-communication. Our zeal for social discipline consigns these men to a permanent nether caste. And yet, since these men – whatever their shortcomings – have emotional and sexual and family needs, including the need to be fathers and husbands, we are creating a situation where the children of this nether caste are likely to join a new generation of untouchables. This cycle will continue so long as incarceration is viewed as the primary path to social hygiene.”

Family disintegration: An estimated 11,000 incarcerated drug offenders, including 1,000 women, are parents of young children. Close to 25,000 children in New York State have parents in prison convicted of non-violent drug charges. As a consequence of losing a parent to prison, these children and their extended families experience psychological trauma, financial deprivation and physical dislocation.

Destabilized communities: The vast majority of incarcerated drug offenders come from poor, inner-city neighborhoods. Paradoxically, the constant removal and return of prisoners (the “churning effect”) make neighborhoods less safe. Recent research shows that the “concentration of incarceration” leads to the further destabilization of our most vulnerable neighborhoods. Columbia University sociologist Jeffrey Fagan and his colleagues have studied the “spatial effects”of high incarceration rates and found that “[i]ncarceration begets more incarceration, and incarceration also begets more crime, which in turn invites more aggressive enforcement, which then re-supplies incarceration . . . [T]hree mechanisms . . . contribute to and reinforce incarceration in neighborhoods: the declining economic fortunes of former inmates and the effects on neighborhoods where they tend to reside, resource and relationship strains on families of prisoners that weaken the family’s ability to supervise children, and voter disfranchisement that weakens the political economy of neighborhoods.”

Loss of political representation: Most incarcerated drug offenders come from inner-city communities of color, but for purposes of the census they are counted as residents of the upstate, overwhelmingly white counties where they are serving time. In the last legislative redistricting, these inner-city communities lost 45,000 residents to upstate, mostly white districts. And because of the state’s felon disfranchisement laws, tens of thousands of black and Latino prisoners and parolees cannot vote.

We have truly come upon a crossroads in our approach to the adjudication and sentencing of drug offenses. We can persist in the “locking up the wrong people for the wrong reasons” (in the words of Thomas A. Coughlin, the former New York State Corrections Commissioner), or we can muster the courage to create a sentencing structure that restores judicial discretion, expands eligibility for alternatives to incarceration (ATI), establishes a comprehensive ATI rehabilitation model – and that reinvests in our most vulnerable neighborhoods the enormous savings that will be realized from cutting the costs of incarceration.

I appeal to you, the state’s legislative leaders, to help lead the movement for comprehensive reform of the state’s drug sentencing laws.