Technology is not a Panacea Against COVID-19

As states across the country begin to lift restrictions on public life and allow businesses to reopen, public officials and health experts are turning to technology to boost their efforts.

Identifying people who may have been exposed to the coronavirus is a critical step to reopening, so it may be tempting to welcome any tool that can curb its spread. But in order to do that, technology must have strong privacy protections. It turns out that what’s best for privacy and civil liberties is also best for public health.

Privacy protections aren’t an afterthought that can be disregarded in times of crisis; they are the lynchpin to an effective technology-assisted program that earns the trust of the public. Without them, we run the risk of putting our health and safety in danger, exacerbating inequalities, and undermining people’s civil rights and liberties.

And especially now with growing calls to radically rethink law enforcement and public safety in the wake of widespread protests and unbridled police violence, any technology used to fight COVID must not increase already rampant discrimination and over-policing, particularly in Black communities.

Already, many companies are pitching their supposedly COVID-combatting services to governments and law enforcement agencies across the country. But these products share two things in common: they don’t operate on individuals’ informed consent, and they aren’t effective as public health measures – they’re just flawed surveillance systems being sold as public health products.

For example, advertising technology and data brokers were quick to provide mass location tracking data at various scales and levels of granularity to national, state, and local governments. This data was mostly surreptitiously collected and shared without notice or consent from affected people. While there is no question such tech represents an intrusion into people’s whereabouts, its efficacy in combatting the pandemic is far more questionable.

That’s because this kind of location tracking fails to help people do the one thing that the CDC recommends: avoid coming into “close contact” for a prolonged period of time with a person who has tested positive for the virus. Close contact is defined as being within six feet of a person for a prolonged period of time. None of the data sources used to collect the kind of location tracking data collected by ad tech and data brokers are accurate enough to reliably identify close contact.

So while this information can provide the government a window into people’s private lives, including where they live, work, and worship, it is not accurate enough to be particularly useful in determining who has been exposed to COVID-19.

For people to use a new technology, they must trust that it’s necessary, effective, and ensures their safety and privacy.

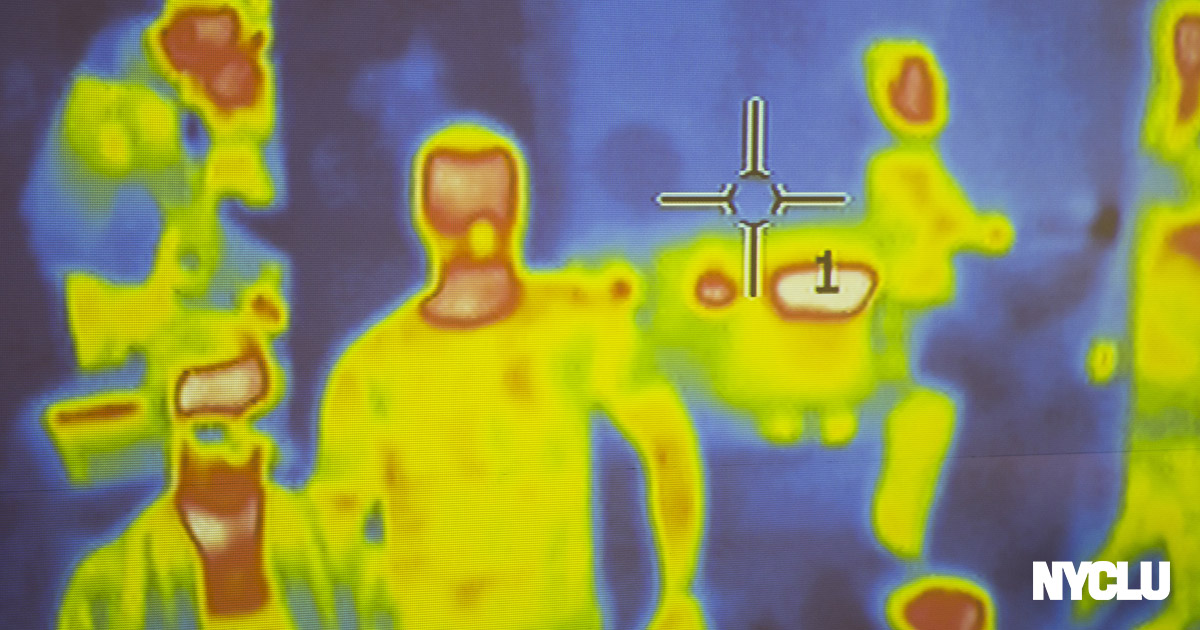

In another worrying turn, a police department in Westport, CT deployed drones coupled with several other surveillance tools: thermal imagery and biometric recognition software such as heart rate, sneezing, coughing, and distance detection.

While these particular recognition systems lack any studies testing their accuracy, similar tools have been proven ineffective and repeatedly show higher error rates for Black people and women – a toxic situation when in the hands of law enforcement agencies, which already disproportionately target communities of color.

Police in New York City have already shown that enforcement of social distancing is racially biased. The deployment of invasive drone technology will likely only increase this problem.

Finally, perhaps the most talked-about technology is Bluetooth proximity tracing, also known as “exposure notifications” apps. Details surrounding the states COVID-19 Contact Tracing Program announced by Governor Cuomo and former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg remain sparse. New York Citys tracing program, which will be managed by NYC Health + Hospitals, will initially start off without a Bluetooth app but officials left open the possibility of integrating such tools later.

For a tracing program to be effective, it must have enough people using the system. And for people to use a new technology, they must trust that it’s necessary, effective, and ensures their safety and privacy.

If people are told, for example, to download an app on their phone related to the virus – without knowing why they’re supposed to do it, what information the app is collecting, what that information is used for, and who has access to that information, – many people will likely decide not to use the app. Even if they’re forced to download it, they will likely undermine its usefulness by leaving it at home when they go out, or finding other ways to limit its efficacy.

With this in mind, any technology used to battle the pandemic should be:

Medically Necessary and Scientifically Justified

There must be clear public health reasons for why information is collected. The development and implementation of technology should also be guided by health professionals who will have insights into how useful certain information is or how effective specific methods are. Any system must be evidence-based and follow a narrowly defined use with clearly set out limitations.

Transparent

People should know why specific technology is being used, what information it will collect and why, where that information will be stored, who will have access to it, and for how long. There should be several ways to audit and review the system to ensure its trustworthiness, integrity, and security.

Voluntary

People should be allowed to opt-in or out of any technology that collects sensitive information about them. Again, this is important not just for privacy reasons, but in order for individuals to trust these systems to give them their data – and therefore for these technologies to work effectively.

Non-punitive and Non-discriminatory

The technology must not be used for any punitive actions and should not be in the hands of law enforcement agencies or immigration agencies.

It should mitigate any bias, misrepresentations, or blind spots and a racial impact assessment should be required before implementation.

Privacy Protective

The amount and type of information that is collected should be limited to only data that is necessary to protect public health. It should be anonymized whenever possible. And it should avoid centralized data storage to the greatest extent possible.

Critically, any collected information should be kept for as short a time as possible. And there should be sunset clauses that dictate when the entire program must end.

Strong Protections

Just as important as who will have access to COVID-19-related data, is who will not. People will be more likely to opt-in to technology if they know that anything collected will only be accessed and utilized for public health purposes under strict rules. Prohibitions should make clear that it will not be shared with immigration or law enforcement or be used for commercial, advertising, or marketing purposes.

Any misuse or violations should be held accountable and public officials should make clear what the penalties are before any technology is implemented.

Building these safeguards in is important not in spite of the public health risks posed by the coronavirus, but because of them. These guiding principles will help make sure technology used to fight the disease is as effective as possible.

For more on this topic, read about the ACLU’s principles and government safeguards for technology-assisted contact tracing.